Mount Wilson is at 5715 feet on top of the steep San Gabriel mountains overlooking the LA basin (and just above all the smog). Its main claim to fame was having for many years the world's largest (diameter) telescopes: first from 1908 the 60-inch Hale reflector and later from 1917 to 1948 the 100-inch Hooker reflector, which was the biggest until the 200-inch was built for Mt. Palomar, near Escondido. We haven't been to Palomar yet, but have seen it in the distance from the top of Mt. San Jacinto above Palm Springs. Like all observatories, there is so much history here!

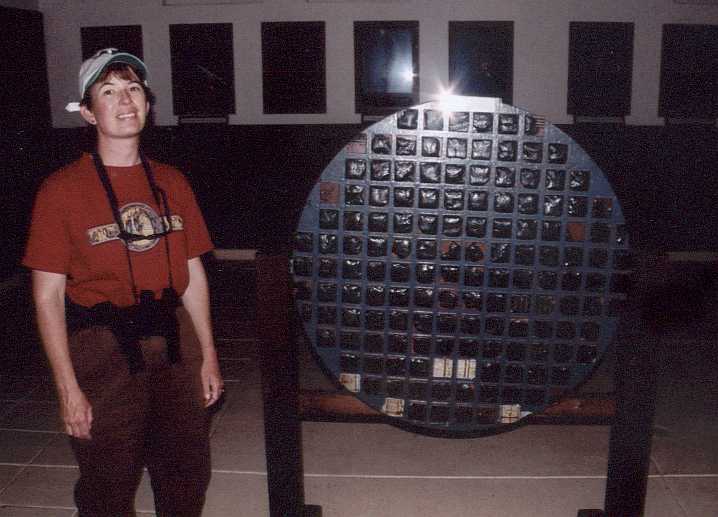

How's that for a mirror making tool?

The 60 and 150-foot solar tower observatories were some of the first dedicated to studies of the sun. Like the Dunn solar scope at the NSO, the domes house mirrors mounted above ground-level atmospheric distortion and trees and send the light down a tube to instruments located on the ground below. Many pioneering studies and discoveries about the sun were made with these scopes.

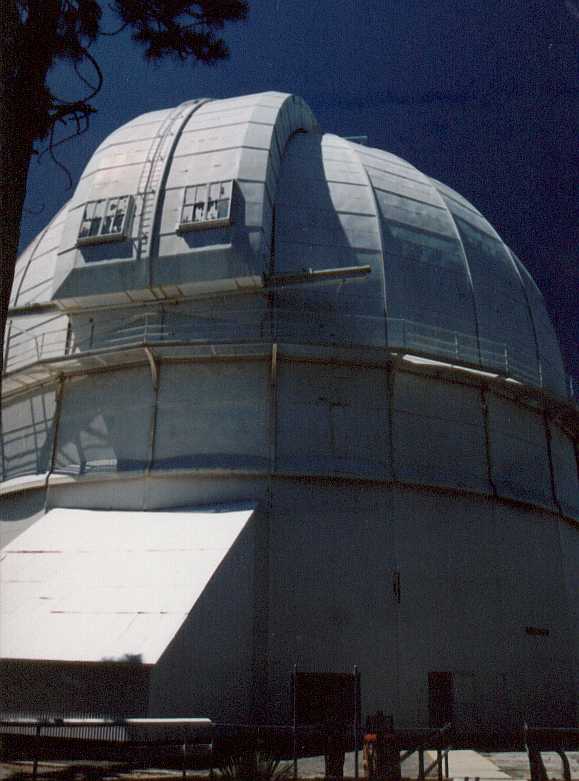

Above is the dome for the 60-inch Hale reflector. Compare this to the "dome" housing the 3.5-meter scope at Apache Point.

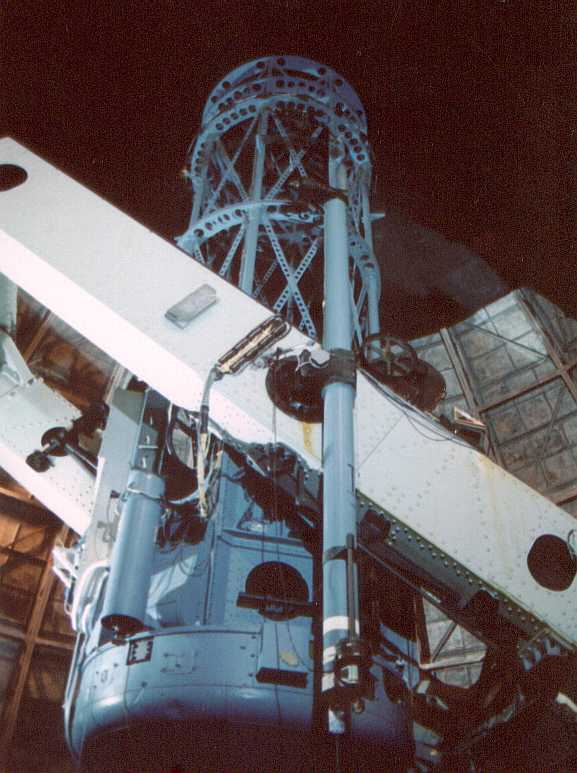

The 60-inch telescope was used largely for pioneering studies of spectral

classification and in adaptive optic technology. In 1957, physicist Robert

Leighton partially corrected, by a factor of 2 or 3, atmospheric blurring by

tilting the secondary mirror several times a second (a technique now

called "tip-tilt" correction). One of the first adaptive optics

systems designed -- Atmospheric Compensation Experiment (ACE)-- was

developed and used on the 60-inch telescope from 1992 to 1995. It is now

used for public viewing and is available to individuals and groups.

This is the old warming hut on the path to the 100-inch dome. Famous

astronomers and others, like Einstein, would hang out in here when it got

cloudy. There's a nice water fountain outside, a necessity in the cool,

dry air at 6000 feet. In the background is the dome for one of several

optical interferometers, whose light is sent down long pipes to one central

place and used to create one image. The flagship project of Georgia State

University's Center for High

Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA) is its optical/interferometric

array of six telescopes located on Mount Wilson. Each telescope of the

CHARA Array has a light-collecting mirror 1-meter in diameter. The

telescopes are dispersed over the mountain to provide a two-dimensional

layout that provides the resolving capability (but not the light

collecting ability!) of a single telescope a fifth of a mile in

diameter. Light from the individual telescopes is conveyed through

vacuum tubes to a central Beam Synthesis Facility in which the six beams

are combined together. When the paths of the individual beams are

matched to an accuracy of less than one micron, after the light

traverses distances of hundreds of meters, the Array then acts like a

single coherent telescope for the purposes of achieving exceptionally

high angular resolution. When fully operational, the Array will be

capable of resolving details as small as 200 micro-arcseconds,

equivalent to the angular size of a nickel seen from a distance of

10,000 miles (over 100 times the resolving power of the Hubble Space

Telescope). In terms of the number and size of its individual

telescopes, its ability to operate at visible and near infrared

wavelengths, and its longest baselines of 350 meters, the CHARA Array is

arguably the most powerful instrument of its kind in the world.

You can see how huge domes got by the late 19th century, even for "just" a 100-inch diameter reflector. All domes are essentially alt-azimuth mounts that move in a different manner than, and independent of, the equatorially mounted telescopes, and thus had to be big to accommodate the telescopes' spindly mounts (see below) and long focal lengths. By the late 1970s, with computers controlling alt-azimuth telescope mounts and the ability to make boxy, very short focal length/very wide diameter reflectors, the domes now just fit tightly around them or just roll out of the way! Compare the domes on this century-plus old site and the Mayall dome at Kitt Peak (among the last of the old breed), to the WYN at Kitt Peak and the larger telescopes at Apache Point.

As shown below, the 100-inch telescope is a classic of early 20th century telescopes, but got to be rather obsolete, it was not used from 1986 to 1994. But subsequent upgrades to its control systems and a state-of-the-art adaptive optics system have rejuvenated it!